A report from Graham Johnson, showing the importance of perseverance at the first control

At the end of July, 40 intrepid DVO orienteers made their way north of the Border for the Scottish 5-Days. A few weeks earlier, two equally intrepid DVO orienteers (that’s me and Val, if you hadn’t guessed) had made their way in the opposite direction on our way to the French 5-Days.

This was the fourth time we’d taken part in this competition which has settled down into a pattern of being held, like the Scottish, every two years, each time in a different area of France, but generally in the south. It was the first time we’d been anywhere near the Pyrenees and the prospect of cycling from one end of France to the other to attend was too inviting to ignore.

O France is normally earlier in July, enabling us to take in both the Scottish and French, but this year, both coincided. It really didn’t take us long to opt for the Gallic alternative. We have never been disappointed by the variety and quality of the terrain on offer beyond the Channel, and the organisers of this year’s offering did not let us down. I say this despite the fact that, two months before the beginning of the festival, we received an email announcing that the event had lost four of its five areas due to concerns of ‘biodiversity’. The outlook seemed pretty bleak for any sort of competition, and we resigned ourselves to undertaking just the cycling part of the holiday. Nevertheless, and remarkably given the short notice, O France 23 went ahead. The organisers were able to find other areas within the same region, the only compromise being that the courses were slightly shorter than they otherwise would have been, a trifling trade-off in the circumstances.

The rival attraction of the Scottish meant that there were only six British residents taking part, the other four, WCOC members including Nick and Janet Evans, formerly of NOC, who transferred from the Scottish to the French following a chance meeting with us in Keswick(!).

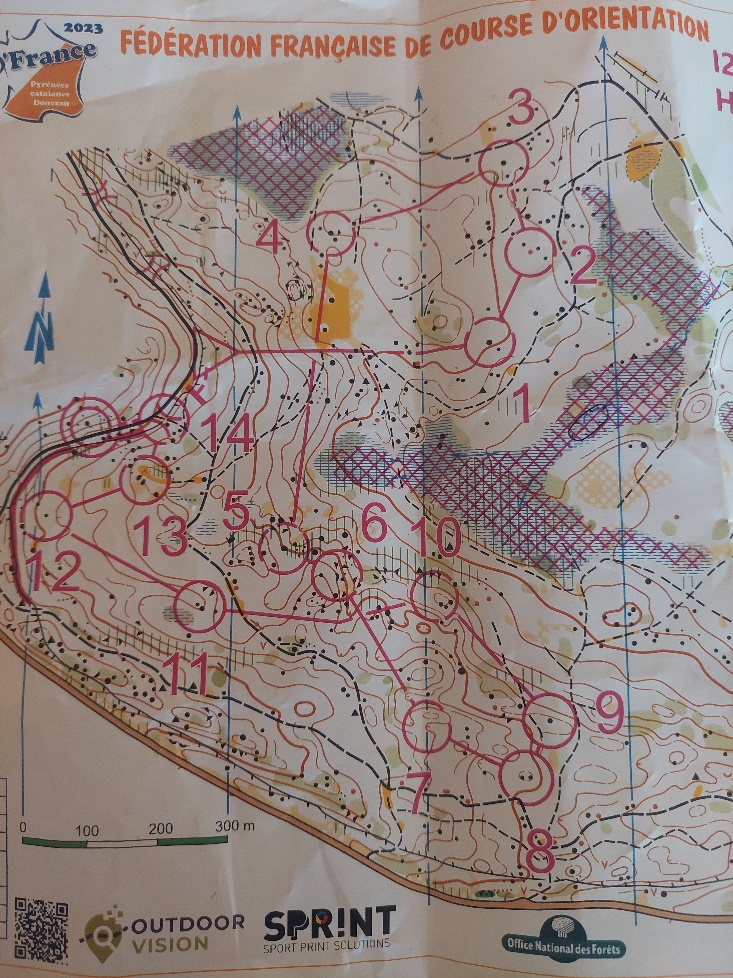

Despite the Pyrenees mountains being, well, mountainous, those at the southern end do take a bit of time to get going. There’s a gradual build-up of altitude, interrupted by forested valleys, so the topography, whilst being hilly, was not as dizzy as you might anticipate. The floor of each area was almost without exception entirely runnable, being covered in ankle-high grasses and similar vegetation, but devoid of anything unfavourable to fast orienteering, specifically brambles, brashings, heather or even bracken. This factor alone made the journey worthwhile.

Scattered amongst the greenery were random boulders of heights up to 3 metres – the areas attracts a lot of bouldering climbers – and these provided the focal point of most of the control sites. The map featured more black dots than a teenager’s chin.

My past endeavours abroad have not been universally acclaimed. My efforts have tended to emulate those of Rangers (we’re talking football here, not Yogi Bear) in that I generally perform adequately in a familiar domestic setting, but as soon as I embark on any sort of European adventure, I end up embarrassing myself such that my interest in further competition rapidly becomes academic, and I eventually return home to general scorn and derision (end of convoluted metaphor).

It looked as though O France 23 was not to provide an exception to this habit. For some reason, I have developed a First Control, First Day phobia, so that last year it took me 65 minutes and 5 km to find it. By my standards, the 2023 version was a dramatic improvement, only 22 minutes, but by anybody else’s, it was still a humiliation. If you can’t spot a 3-metre-high boulder 400 metres from the Start, what hope is there for the rest of the week? (The disorder runs in the family; it took Val four days to shake off her First Control Blues).

Rather than the Scottish formula of Best 4 of 5 to count, O France opts for the Final Day Chasing Start, reserved for those who have managed, over the first four days, to remain no more than 45 minutes off the winner’s coattails. That’s an average of only just over 11 minutes of mistakes a day. My Day 1 finishing time of 72 minutes meant I’d used 42 minutes of my 45, and I already required a miracle to avoid relegation to the ranks of the Day 5 also-rans.

One of the peculiar features of a French print-out is identification and listing of course errors. I have no idea how this works, but I suspect that the computer works out your average speed per control and then calculates by how much your worst controls fall short of this standard. To preserve paper, they restricted my errors to just the worst five. I found this practice intensely annoying. First of all, I already knew very well which controls were a personal fiasco, and confirming them served no purpose at all. Secondly, the last thing I needed off the back of a disastrous run was some computer identify my failings in precisely calculated form. It did nothing for my confidence, let alone outlook for the following days.

My miserable series of performances were thankfully alleviated by the Rest Day Urban, which, as in Scotland, played no part in the main competition itself. At the Scottish, I normally give this a miss, conserving energy for the last two days. However this Urban was to take place in Puigcerda, a village on the France/Spain border, and was organised by the local Catalan O-Club. The novelty was too good to miss, and Val and I both signed up.

The logistics of even getting to the event required some ingenuity. Having cycled to Perpignan, we’d hired a van to take us and our bikes into the Pyrenees. On picking the van up, we were advised that to take it out of the country would incur a cost of a further 55 Euros. Not particularly inclined to boost Enterprise’s profits, we solved the conundrum by driving our van to the village on the French side of the border, parking it, removing our two bikes from within and cycling the rest of the way. This journey was given added peril by our route passing immediately adjacent to Llivia, an enclave or piece of Spain floating independently in France. Who knew?

The organising club had obviously never taken on anything of this size before and the descent (strictly speaking ascent, since the Urban was on the top of a hill) of around 1,500 orienteers on Puigcerda was way outside their experience. Advance details were sparse; we knew only a) our start times and b) where the event centre was, which makes something of a nonsense of those event organisers who produce pre-event details rivalling Marcel Proust for prolixity. Our three minutes in the starting pen turned out to be a preliminary not to the event itself, but to a five-minute walk to the pre-start. Nobody had troubled to explain this so the initial stages of the event were marked by chaos. In addition the map didn’t show us where the route to the Start triangle was so, on retrieving our maps, we knew where the Triangle lay, but not where we were on the map to get to it!

(The second photo above is taken north looking south – I think!).

This anarchy was mirrored at the Finish, because when I received my printout, my time was 2 minutes more than the time on my watch. Not to be outdone, the organisers then contrived to show my overall time on the results screens as 4 minutes less than my printout. This had the effect of making my time to the first control -7 seconds – a personal best which I am unlikely to repeat.

These various mishaps never fazed the local club members who to their credit shrugged off the glitches, their good humour unabated. The hiccups did not detract from the excellence of Puigcerda as a venue for an urban event. The old town, founded in the 12th century, had largely preserved its mediaeval appearance. Its lofty position ensured our courses were regularly interrupted by a series of stairways as we navigated our way up, down and through Puigcerda’s narrow byways (see above).

Somewhat to my surprise and confounding the formbook, my printout indicated I was in first position. I was initially convinced that this was another blunder, but the anomaly not only survived the removal of two of my controls from the results following appeals, but was fortified by it since one of the controls was the site of my only serious error. This was turning out to be my lucky day, and it was finally crowned by the discovery that trophies were to be awarded to the course winners. Thus it was that I returned from what I’d approached as a casual interlude bearing a rather splendid memento of the occasion. Every dog has its day, and this was mine.

Somewhat to my surprise and confounding the formbook, my printout indicated I was in first position. I was initially convinced that this was another blunder, but the anomaly not only survived the removal of two of my controls from the results following appeals, but was fortified by it since one of the controls was the site of my only serious error. This was turning out to be my lucky day, and it was finally crowned by the discovery that trophies were to be awarded to the course winners. Thus it was that I returned from what I’d approached as a casual interlude bearing a rather splendid memento of the occasion. Every dog has its day, and this was mine.

In the main competition, having languished in 59th position (out of 61) after Day 1, I settled down to my usual habit of producing an undistinguished run characterised by at least two horrendous errors, thereby squandering the benefits of what preceded and followed. I’d dragged myself up to 46th overall, a mere hour and a half behind the winner. Val was meanwhile locked in life-or-death combat with Janet Evans, being 19th overall to Janet’s 18th, each finishing respectively 17th and 15th.

Chasing Starts are a practice which have sadly all but vanished from the British orienteering scene. On balance I’m a fan, though on previous occasions, I have failed to shine under the prevailing conditions, my navigational skills tending to desert me in my hour of need; I have rarely finished higher than I started.

At O France, once the first 20-odd M65s within 45 mins of the winner had been set off, the remainder of us followed at 30 second intervals. This preserved some incentive to chase the most adjacent competitors in front, and avoid those behind. In fact all 2,500 orienteers were funnelled through the same start lanes in rapid succession. This seemed to presage the sort of chaos last seen on the streets of Puigcerdà, but somehow it all worked out.

For the last two days, we had moved further up into the Pyrenees so that the terrain was marked by an increase in both contours and the intensity of green. Though they never lost their enjoyable runnability, the areas did become more recognisable to the British orienteer. Maybe this was the difference, because I found controls popping up where I expected them, and even a gamble that I really had no right to expect to succeed paid off. I finished triumphantly in 5th position. OK, this only meant I’d caught up 7 places overall, but even the harshest judge would surely have to concede this was a pretty remarkable performance from someone not used to it. No-one but no-one at O France managed both a 59th and a 5th position so maybe, just maybe, there is hope yet.

Graham Johnson